Pastiche, Irony, and Thinking Differently

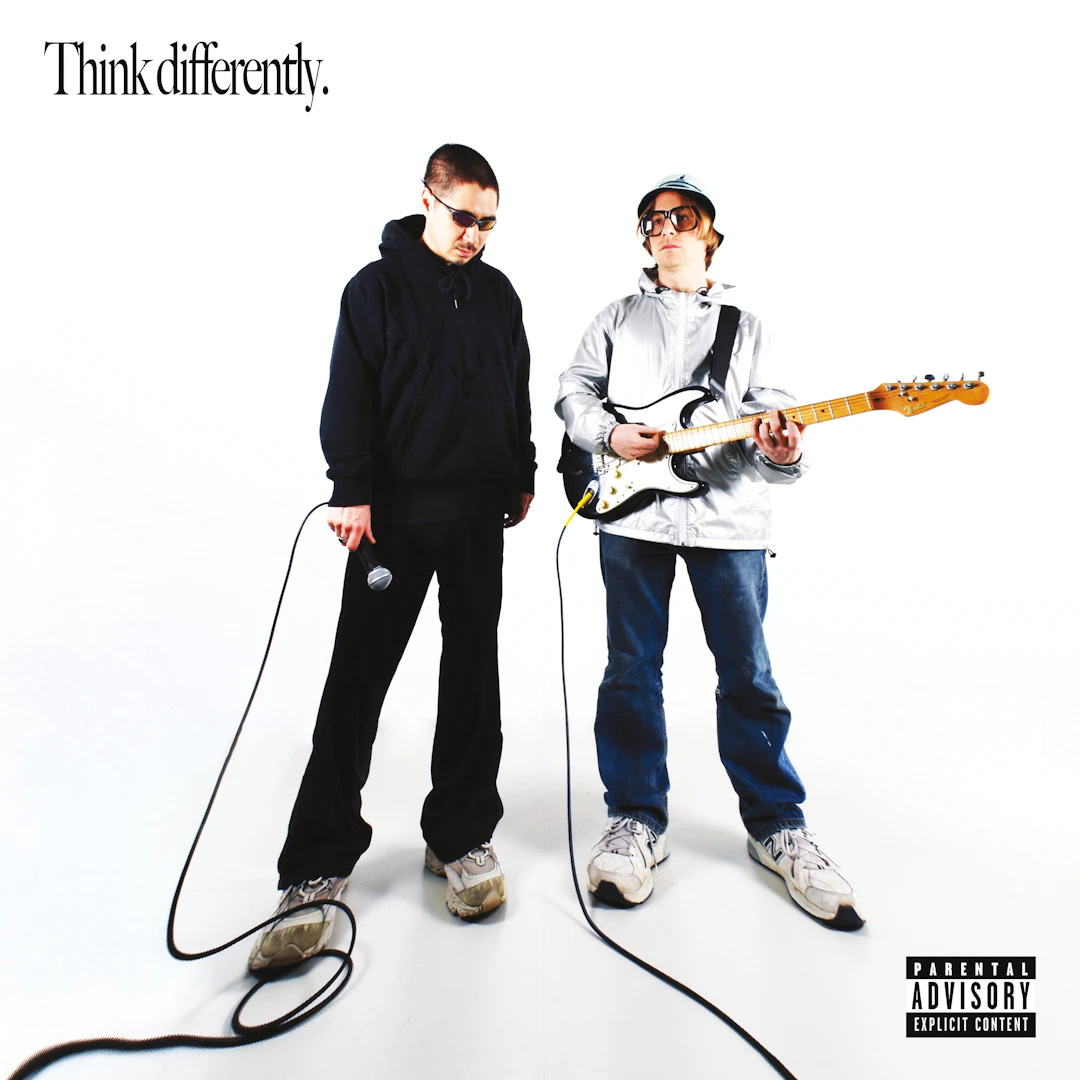

An essay for something forthcoming on the occasion of Callahan & Witscher's 'Think Differently' LP.

Irony and pastiche are two of the most prominent aesthetic categories these days, and they are linked in a couple core ways.

Irony functions by juxtaposing what is said with what is meant. While it can be deployed with good-natured playfulness, irony is frequently associated with cynicism, critique, and satire. It simultaneously constructs and draws attention to a relationship between the speaker and the social practice, milieu, or institution being ironized. When an online leftist makes a joke about 9/11, they ridicule the double standards of American exceptionalism given the country’s horrendous history of military “interventions” abroad. Regardless of political alignment, the person making an ironic quip often frames themselves as a dissident or outsider in regard to a given normative standard.

We can identify a remix of the ironic–unironic binary pair in the term “irony poisoning,” whereby irony sublates sincerity, and taboo jokes transform over time into taboo beliefs. Another example is the meme construction, "I'm neither joking nor serious but another secret third thing." This statement gives form to a kind of nuance not afforded by the strictly limited choice between “serious” and “not serious.”

The history of art is full of examples of the cunning elaboration of a “secret third thing,” but the term also has a deeply contemporary resonance. The emotional register of sincerity connotes a series of upstanding, humanist communicative standards: sharing one’s feelings, being honest, using rational argumentation in order to arrive at the truth, connecting with others, and so on. Meanwhile, irony has negative, anti-social connotations, and it could reasonably be charged with “promoting division.” A rhetorical style that synthesizes each term of the binary might simply propose a measured adaptation to the intensified experience of complexity found in mediatized contemporary life. We can see this in the way friends share ironic media objects with one another as a means of communicating about sincere sentiments or commitments. It is possible to sincerely use irony, or to be ironic, sincerely.

Pastiche has a similar, complexified status within contemporary artistic production. I will focus on its role in music in particular, and on questions of originality, homage, and “revival.”

One popular framework for considering the latter set of issues is provided by Mark Fisher, who argues that the post-2000s surge of pastiche, hauntology, and various subgenre revivals can be attributed to capitalism’s “slow cancellation of the future.” Another influential systematization of these questions arrives via 70s postmodernism and the artistic practices of the Pictures Generation. To summarize in the broadest possible strokes, this line of thinking proposes that the death of the author, the status of the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, and the collapse of teleological “grand narratives” all undermine the viability of the very notion of originality.

Sherrie Levine is a canonical example: she took photographs of other people’s photographs, and quoted other people’s writing in press releases. As if seeking to empirically verify Benjamin’s famous account of photography, her works forcefully demonstrate that the power of a photograph has less to do with the person taking it than what is in it.1 This upends the typical privileging of the artist as secular oracle, seeing what others do not and showing things that others cannot. Levine’s practice foregrounds the fact that a photograph only ever exists as a copy: a painting might be reproduced in a magazine, but we all know the real one is in a storage facility somewhere. Levine’s 1981 work After Walker Evans is indistinguishable from Evans’ original, which suggests that it doesn’t really matter who snapped the photo: she places emphasis on the act of looking, the affordances of the medium, and the mode of circulation, positioning these structural phenomena at a fundamental, privileged remove from authorship and originality.

In the mid-to-late 2000s, LCD Soundsystem, née James Murphy, “stole” core musical ideas from Killing Joke, Iggy Pop, and the Velvet Underground, but his approach would never be confused with Levine’s. He uses this source material not to stage a critical intervention but as a means to tell his own story, to dramatize his personal crises and desires. Levine sought to decenter the subject and demonstrate the ways it is unwittingly spoken through by the other, but Murphy isn’t too worried about that kind of thing. His first song lamented how under-appreciated his amazing record collection was. Sure, there is some degree of irony in his performance, but only so much, which is what makes the song compelling.

If you haven’t already, listen to The Pool’s “Jamaica Running.” The resemblance between this song and LCD Soundsystem’s “Dance Yrself Clean” is totally undisguised. Once identified, the track’s frisson is re-centered upon the brashness of Murphy’s approach to homage, which diverges significantly from standard approaches to the “cover song.” Conventionally, the artist doing the covering is expected to unambiguously make the song their own through decisions at the levels of instrumentation, arrangement, production, and/or performance.2 Consider Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of “All Along the Watchtower,” “Respect” by Aretha Franklin, Xiu Xiu’s “Fast Car.” Murphy goes another direction: the thing truly setting Murphy’s work apart from his source material is the fact that he is the one singing, utilizing the source material for what might be describe as his world-building practice, where the line between piracy and homage is actively blurred.3 LCD Soundsystem conscientiously used vintage analog equipment, and almost never used contemporary-sounding digital software effects, editing, or compositional styles. (Timbaland and Autechre are obvious contemporaneous examples.)

In recent years, unapologetic pastiche has increasingly become the norm. This is particularly the case for genres including house, techno, rock, and “experimental music” – a term that frequently indexes an ossified set of formal characteristics specific to ambient, electroacoustic, noise, and industrial musics.4 In the NYC “downtown scene,” pastiche is everywhere. In the vein of Murphy, an artist like The Dare seems uninterested in “musical innovation” as a process of creating previously-unheard sounds, but this doesn’t stop him from having some solid songs. Creativity in instances like this is expressed not in the material construction of sound, but its context, its circulation, and the memories and fantasies it evokes.5 We see artists working to generate and stylize a context in which a song might exist, intentionally or fortuitously finding the song-form positioned in relation to attention networks and meme cycles.

We see the aggregative practices of the creative director, DJ, and curator adapted to artistic production: shifting other people’s stuff around in compelling ways, and adding your own signature in the process. The aggregator must have a specialized approach to various time-scales, stylizing not just a set of materials at a given point in time (synchronically) but over time (diachronically). Which is to say, it matters how often an aggregator changes their style, adapting rapidly to the times or sticking to a core sensibility.6

Aggregation has become less of a second-order process – conceptually distinct from the actual creation of work – and more of a privileged first-order production process. While it’s true that there is a lot of bad work in this vein, it would be straightforwardly misguided to write it off entirely. Bobby Beethoven, formerly known as Total Freedom, is an example of how this process can be used to produce work of the very highest quality. (It is worth mentioning that when I interviewed Ashland in 2015, he said he was not an artist.)

In many contexts, pastiche-based art serves a concrete social function: young adults move to Bushwick in order to fulfill a fantasy of playing in an indie band, where “indie” indexes a relatively fixed set of aesthetic methodologies and forms. Following Thea Ballard, we understand that indie rock provides a context and predefined set of social practices for normative social rituals.7 It offers the comfort of secure identity and an easy-to-understand set of norms for creative expression, spectatorship, and relation. There are also many divergences from this widespread standardization, of course: Alex G is clearly influenced by Pavement, but his music does not merely restate the influence.

Given that attention is a key metric driving the contemporary artistic economy, we can understand pastiche as an efficient allocation of resources. If you had a hit white label in the 90s, you could make a decent amount of money without considering the tastes of listeners beyond your immediate scene, but this is no longer the case. Indeed, pastiche is probably also the easiest kind of art to make: the democratization of production and publishing tools along with endless resources such as YouTube production tutorials and r/DrumKits make it easy for the average Joe to produce music and sound like whoever they want.

People today are also more likely than in the past to think of themselves as artists, or at least as people with artistic tendencies. The subject position of the “bohemian creative” has become more desirable and accessible in recent decades; the number of art degrees awarded in the U.S. nearly doubled between 1990 and 2015. The federal Bureau of Economic Analysis found that Arts and Culture economic activity accounted for 4.3 percent of GDP, or $1.10 trillion, in 2022; the G20 says that it could be worth up to 10% of global GDP by 2030. We might also consider the influence of the humanities as one of the era’s dominant pedagogical systems: it encourages students to develop interdisciplinary “creative thinking” skills, flexibly amenable to advertising internships, student film production, and the study of Ancient Greek philosophy.

***

Think Differently elaborates a series of secret third things. This is music about music, but it is far from strictly conceptual in nature: the album works because it carefully attends to the level of sensation, which is to say that it is real pop music.

Thematically, the album engages the trials and tribulations of loving something – music – that doesn’t love you back. The industry is a tragicomedy, and the critical apparatus is generally quite disappointing; Think Differently suggests that nothing is worth affirming except music itself, and the small communities that seem to share your values. The record stages a fantasy of exit, and the inability to do so for economic and personal reasons. The staging itself – the song – belies the stated desire, compulsively elaborating amorousness for music in the form of fantasy.

Discussing a recent, well-known, pastiche-based song about sex, Aria Dean recently said that its most striking feature was in fact its sterilized asexuality. She has pointed out a contradiction worth reflecting upon. Although it might be articulated with unshakeable confidence, good pop music tends to require some degree of vulnerability in order to meaningfully stage the suffering/desire pair and its relation to fantasy, whether that has to do with utopia, sex, politics, violence, anti-sociality, or whatever. This vulnerability might even express itself negatively through the unwillingness to narrativize itself. The song in these instances is thus in some core sense beyond the artist’s control as an index of swirling pressures. We might identify this forever-open question of what a song wants as a kernel that transcends distinctions between repetition and originality, irony and sincerity.

See Crimp’s writing on Levine.

See Thea Ballard’s 2021 essay, “What a Beautiful Feeling, Crimson and Clover: Emotional Listening and Compositional Pleasures” for its sharp analysis of the cover, the commodity form, and the social function of popular music.

Murphy is open about his admiration of Bryan Ferry, whose first solo album post-Roxy Music consisted entirely of covers. Ferry has referred to these renditions as “readymades”: “[The term “cover song”] sounds like a stallion covering a mare or something,” he said in a a 1993 interview with the Independent. “It suggests imitation, like a karaoke record.”

My friend Webb Allen has suggested a compelling framework for thinking about pastiche: the self-insert genre of fanfiction. The term is self-explanatory: a non-professional writer loves a piece of art, and writes themselves into the world.

Rosalind Krauss famously notes the fraught and dialectically generative interdependence of the repetition-originality pair in “The Originality of the Avant Garde.”

David Joselit’s prescient 2013 essay “On Aggregators” is a key reference here.

Thea’s essay offers a lot of nuance exceeding the scope of the point I’m making here.