1.

The Netflix show Stranger Things used Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” in a new episode. I spend about an hour a day on TikTok and I’ve heard it used in a handful of very different videos. Since the song’s recent re-popularization, fans have uploaded numerous edits of the song, adjusting it to play at different speeds. Social media consumers will recognize the time-editing of popular music as an extremely common user practice.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

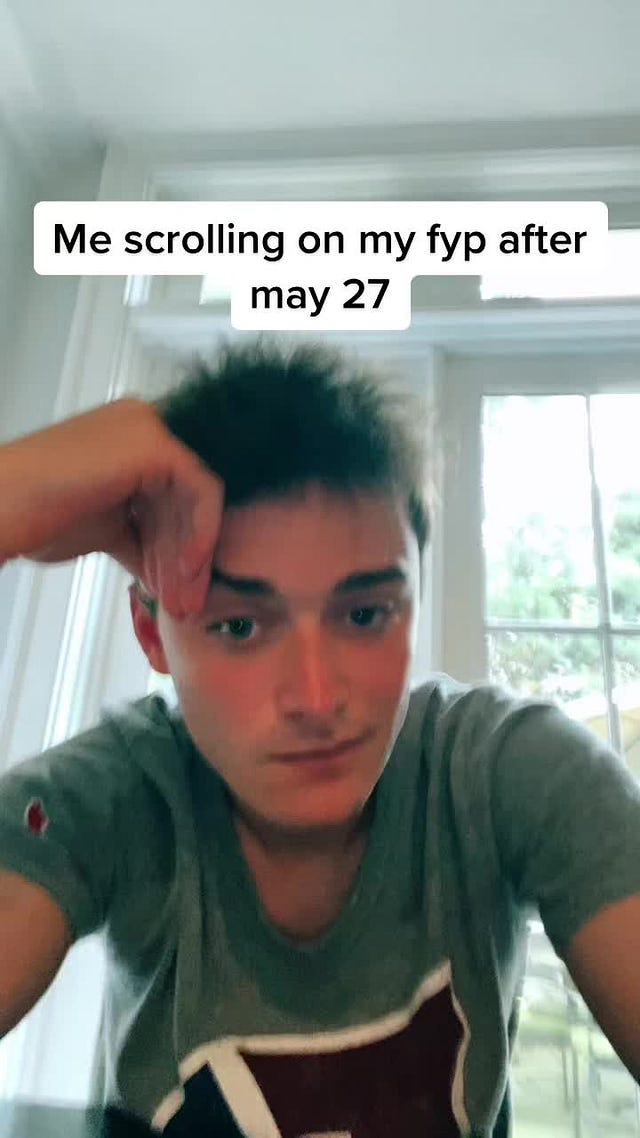

Noah Schnapp, one of the actors on the show, recently posted a TikTok about the phenomenon that’s kind of laborious to describe in natural language but extremely easy to understand within one second of viewing. In the video, he acts out the motions of scrolling down a feed while short clips of Kate Bush’s chorus play in rapid sequence, all at different speeds. On a strictly melodic level, the sound briefly resembles Schoenberg’s twelve-tone music before quickly disintegrating into sonic pollution. The video’s caption reads, “They’re too quick with the sped up versions,” and there’s a text bubble in the video which reads “Me scrolling on my fyp after may 27.”

While listening to the clip it becomes impossible to remember which of the snippets is playing at the “correct” speed. The self-evident truth of what “Running Up That Hill” sounds like is unlocked and kicked around like a soccer ball on a pitch. In a funny turn, the clip’s audio recalls post-electroacoustic music from roughly a decade ago, specifically something that might be associated with the experimental label Editions Mego and/or a James Ferraro-esque zone. Back then it would have been a sound work composed from a “post-Internet” point of view, paying tribute to the vertiginous, disorienting qualities of life under late capitalism, and now it’s background audio for a massively popular funny video.

Stylistically, these sped and slowed approaches are reminiscent of two formal predecessors in particular: Nightcore on the one hand, and Chopped and Screwed music on the other. These two styles were themselves the product of artistic intentionality – music-making as a form of meaning-creation – but this form of TikTok editing is the product of a more impersonal mode of information-dispersion. The process of organizing sound into music finds itself supplanted by the automated capacities of a UI effect designed to facilitate “discovery” in the TikTok sound-world.

Songs are made to shed their baggage and become raw material to be utilized by users to convey relatable emotions, tell stories, or make jokes. They are re-engineered as essentially incidental regardless of how they were created. The artists Jeff Witscher and Jack Callahan have caught on to this phenomenon, and their recent ISSUES (What Happens on Earth Stays on Earth) LP teases out some of the strange and thrilling undercurrents of late-Web 2.0 memetic sound-forms. Now that I think about it, their captivating performance of that same work at Union Pool earlier this year likely spurred a lot of these thoughts.

The other side of this musical time-modulation phenomenon is the type of upload where popular songs are looped for an hour or ten. This time-suspending social practice has spawned changes in popular songwriting which I wrote about last year, yielding a form which can be described as the Endless song.

The standard critical response to this user-driven, sped-up and slowed-down edit form would be something along the lines of, “This marks the end of artistic sovereignty, of the importance of original artwork, and the beginning of the true dominance of the copy, where the border between cultural producer and consumer is completely eroded.” This is not false but it describes a change that happened decades ago. We’re on to something different now.

These user-uploaded edits reflect the changing shape of time and underlying conditions of temporal deferral. I’m following up here on my essay about perpetual futures contracts, where I detailed some of the ways in which speculation rearranges temporality from the inside out. Traditional derivatives use the uncertainties of the future to construct prices in the present – following Elena Esposito’s analysis – but with the more recent invention of perpetual futures users can now formally define the future so that it never truly arrives. We have reached a striking period in the history of finance where derivatives contracts do not have to be tied to any date in particular; rather, they can be perpetual, or perhaps more to the point, eternal.

This innovation effectively radicalizes capitalism’s extant mandate to operationalize the present for the future through the pursuit of maximal speculative returns, which is just another name for “risk management.” These novel financial instruments exploit and intensify the latent desire to “Make Every Moment More” – the slogan used in a recent FanDuel ad dramatizing the power of prop bets, a form of wager that is indifferent to a game’s final score – and as a result time finds itself unmoored. These looping and time-bending forms arise when users attempt to take time into their own hands, hoping to reshape its textures and timbres. The fact that “Running Up That Hill” is itself about a wager – a deal with God – is worth appreciating.

This idea of a perpetual futures contract is still relatively niche, and while there are probably fewer people gearing up 100x-leveraged perps during the bear market than a year ago, their effects are locked in. Just like most people don’t know that negative interests rates are not only real but prominent in today’s financial system – making possible through their backwards-seeming logic a significant amount of everyday economic activity in a post-2008 context – the relative obscurity of perps allows them to ingest and modify common sense in relative isolation from what is discursively codified as “common sense.”

2.

I’ll say more about the “incidental” form of music I mentioned above. This incidental kind of artistic production whereby a machine does most of the artistic labor is set to become significantly more popular with the popularization of AI-based tools. You can just instruct a machine to make something extremely specific and it’s able to return a decent approximation, as the current wave of prompt-based Mini Dall-E images on social media makes clear. Imagine being the future AGI itself and looking back on this practice, surveying all these weird, blurry images, trying to make sense of what specifically we found interesting in them.

3.

One of my favorite Tik Tok phenomena right now is the thing where a user will go live and then commit to singing or rapping the names of all the people in the comment section. The more people that join the stream, the fewer they are able to get to, and the more insistently you have to type your own name in order to try to get the creator’s attention. These creators are essentially turning themselves into robots for views, driven by a simple prompt which they must single-mindedly execute for hours on end, without rest. This practice, combined with the mandate that the artist literally sing their fans’ names over and over, feels distinctly of the cultural moment.

4.

In Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller,” he makes a brief mention of a sundial in Ibiza. He is interested in its inscription Ultima multis, which means “the last hour for many.” Obviously Ibiza was a very different place in the 1930s than it is today, but since revisiting that passage I’ve become fixated on this idea of this Ibizan sundial in the present. A sundial to be read in the post-EDM twilight, surrounded by revelers returning to the island in the summer, post-COVID. Watching these TikTok livestreams, typing in my name and double-tapping to “heart” the content, I’m getting a glimpse. I can feel the sun’s rays.