Mp3 as instrument: notes on F1LTHY's approach to production

Technical and historical analysis. The artist is known for his collaborations with Playboi Carti, LUCKI, Bladee, and more.

If you listen to rap, you are familiar with F1LTHY, née Richard Ortiz. The Philadelphia producer is one of the primary sonic architects behind Playboi Carti’s Opium collective, which includes Ken Carson, Homixide Gang, and Destroy Lonely. He produced a significant portion of Bladee’s last album, Cold Visions, picking up where their previous long-form collaboration, Working on Dying (2018) left off. In 2021, he released a collaborative album with LUCKI. In 2022, he produced Lil Yachty’s 2022 viral hit “Poland.” He has also worked with Black Kray, Drake, Yeat, and many others.

Ortiz was a relatively underground figure in rap until Carti’s 2020 album Whole Lotta Red, of which he produced a significant portion. Four years later, it’s easy to forget how blasphemous the album’s crude, blown-out sound was at the time. Through his contributions, including “Stop Breathing,” “Rockstar Made,” “New Tank,” and others, Ortiz made a lasting imprint on the sound of rap. There are many contemporary artists working in the wake of Ortiz and Carti’s collaborations, but the most prominent include LAZER DIM 700, OsamaSon, Xaviersobased, and Nettspend.

To appreciate the innovations of F1LTHY’s sound, we can situate his approach within the historical development of trap. In the early 2010s, producers including Metro Boomin, 808 Mafia, and Mike Will Made-It foregrounded a distinct approach to maximalism and complexity within software-based rap production. Rarely working with samples, but rather composing from scratch using MIDI, these artists introduced sound design and experimental plug-in manipulation to their processes, resulting in dynamic sound-worlds that modulated their spatiotemporal axes from the inside-out. In order to be competitive, producers showcased mastery over their software tools, making trap of the aughts sound minimal and reserved by comparison.

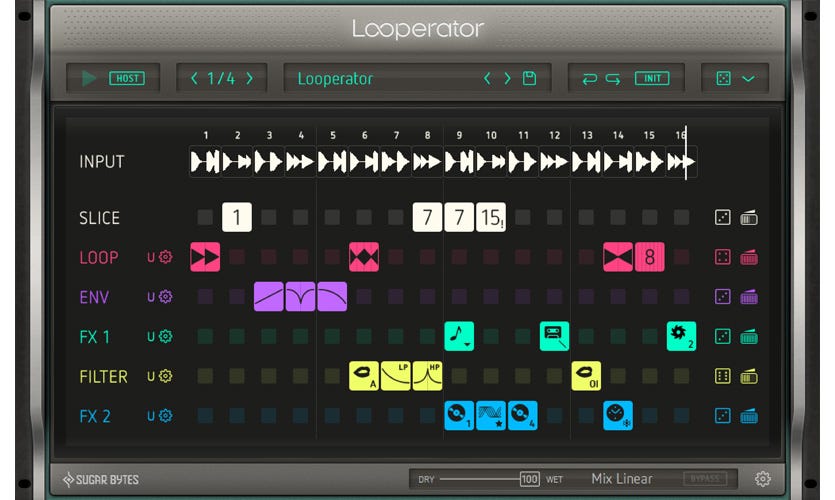

At the level of the waveform, producers of the earliest trap – T.I., Jeezy, Gucci Mane – generally had less at their disposal. Consumer-facing digital synthesis tools experienced a renaissance in the mid-2010s: Serum, Massive X, and Omnisphere 2 offered users unprecedented control with the introduction of advanced wavetable synthesis capabilities, along with sophisticated filtering and effects functionality. With these VSTs, bedroom producers could produce one-of-a-kind, highly complex sounds combining multiple waveform types with relative ease. Meanwhile, tools like Gross Beat, Looperator, and Effectrix streamlined the process of applying filters and effects at the level of the individual note, making it possible to generate substantive variation throughout a measure in a few seconds. Consider the ornate arrangement of Future’s “March Madness”: dynamism is unceasing.

We should understand Atlanta’s rapid sonic development within contemporaneous market conditions. The 2010s saw an acceleration of rap production’s industrialization: beatmakers claimed to make 100 beats in a day, sending 20 instrumentals to a rapper in hopes of locking in a single placement. The instrumental rap marketplace expanded and became oversaturated with platforms like Beatstars and looperman. Songs like “Sicko Mode” became possible, drawing upon the market’s infinite industrial reserve army of stems to create multi-movement songs-within-songs. The “type beat” formal construction was also popularized during this period – Chief Keef famously made “Citgo” after searching “Finally Rich type beat” on YouTube.

F1LTHY cites SpaceGhostPurrp's as a source of inspiration in interviews, particularly the 2011 mixtape Blackland Radio 66.6. At the same time that Mike Will Made-It and Metro Boomin pushed trap into baroque, technologically accelerated territory, SGP went in the opposite direction. His music from this period is raw and rudimentary, to striking effect. If Atlanta actively sought to actualize unheard sonic potentials, SGP affirmed the negative at every opportunity. His productions are artful specifically for their lack of preciousness. It was easier than ever to make beats at home that sounded “professional,” but he chose to sound DIY, embracing misanthropic mysticism and paying homage to lo-fi Memphis rap cassettes from the 90s. One can also hear the indirect influence of Soulja Boy in F1LTHY’s sound, and in contemporary rap generally – tracks like “Wuzhannanan” or “Pretty Boy Swag” simply wouldn’t hit as hard if they were produced and mixed according to normative professional standards.

We might understand Ortiz’s approach as a synthesis of these opposing tendencies. But what does a typical F1LTHY beat sound like? Heavily distorted, with the levels generally pushed as far as they will go. The last thing he does is over-produce: any bedroom producer with basic competence will be able to recreate the basic MIDI patterns of his productions in five minutes. (Imagine trying to do this with “March Madness,” even if you knew the exact arpeggiator patch that Tarentino modulates throughout the track.) Some of F1LTHY’s sounds take on an 8-bit quality because of the way he applies distortion to relatively simple waveforms, which one-dimensionalizes the timbral complexity of its object – whether it’s a synth or a drum – by smothering it, eradicating the fidelity of a signal. He never uses the kinds of dramatic or gesturally abstract sound design motifs common in Atlanta rap. The sonic profile of his work is willfully reduced and straightforward.

To hone in on what Ortiz does, let’s compare one his rage productions with a “classic” distorted rock song, Blue Cheer’s proto-punk tune “Summertime Blues,” or Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” The guitar is distorted a lot, while the bass is distorted a little less – not so much as to overwhelm the sense of low-end rhythm section functionality with atonal sonic character. The drums are almost never overtly overdriven throughout the entirety of a rock song, with the exception of some intentionally “experimental” recordings; compression might run a little hot so the mix glues together – one can hear something like this on Bad Brains’ “Sailin On” – but a totally distorted cymbal or snare is pretty unusual, with the exception of willfully bad-sounding live recordings of hardcore bands.

All of this is to say that even the most trad sound engineer can still find distorted rock agreeable, because it is not completely at odds with the common sense of “good music production.” Let’s take a second to define key conventions of the latter, as it is difficult to fully appreciate F1LTHY’s approach without understanding the standards he chooses to ignore.

According to general audio engineering common sense, mixing and mastering constitute the process whereby a piece of music is sonically refined in order to sound “professional.” Mastering engineers typically work on songs in their entirety, whereas mixers tend to focus on a song’s individual components at a lower level of aesthetic organization. Very generally speaking, producing is considered more of an art, while mixing and mastering are considered more of a science.

The dominant model of music mixing pursues an ideal somewhere between spatiotemporal balance and atmosphere. This is achieved by tweaking the volume, sonic character, and stereo positioning of a song’s individual components – drums, bass, vocal, whatever – in order to create harmonious arrangements. If a song has elements that occupy the same frequency range, they should be mixed so that they do not get in each other’s way. The mixer might use EQ to adjust the frequency range of a given signal, or compression to modify its perceived loudness. These same technical processes are frequently also core components of the music production process, as effects applied to a raw signal.

Mastering, more so than mixing, might be defined as the craft of producing artisanal audio files. It seeks to give every song on an album a consistent sonic profile, and to make them sound as good as possible in every listening environment, from earbuds on the subway to hifi audio systems. Mastering typically maximizes loudness without adding unwanted distortion, removes unwanted sonic artifacts, and adjusts the sonic profile of a recording to make it consistent with the standards of its genre. If a club producer sends a mastering engineer a track without a punchy low-end, then the engineer will likely readjust the sound so that it more closely aligns with the sensory model that the audience expects.

If a song is mixed and mastered in such a way that volume levels exceed 0 dBFS, it starts to produce digital distortion artifacts, including clipping. Ever since the 90s, popular music has found itself embroiled in what are known as the “loudness wars,” fought between technicians with “common sense” and those producers and engineers who push for ever-louder tracks by increasing overall loudness and compressing dynamic range, seeking an ever-more “exciting” sound. Common examples of loudness war perpetrators include Taylor Swift’s Red (2015), the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Californication (1999), and Oasis’ first two albums.1

Conventional audio engineering turns up its nose and upholds qualities of fidelity, balance, depth, and clarity. F1LTHY’s music has none of these qualities: his characteristic sound is specifically achieved by pushing skin-tingling levels of clipping into his productions such that Oasis sounds relatively tame in comparison. Individual components struggle against the smothering effects of digital distortion, arriving in the final mix in fossilized form. F1LTHY achieves these particular effects through a sophisticated approach to network design: his snare, high hats, and synths frequently take on itchy, electrocuted timbres when they are channeled into the same bus track as a chord progression or an 808. He takes a non-standard approach to a typical mixing procedure across genres: multiple, distinct inputs are consolidated into a single output track, where they are subjected to a single set of effect parameters.2

Generally, the inputs sent to a bus track are arranged, mixed, and EQd so they do not noticeably clash with one another. If inputs occupy similar swathes of frequency content, they compete for the ability to send signal into the final mix, carving chunks of sound out of one another in the process. Sonic overlap can lead to muddiness or a visceral increase in loudness, which leads to distortion, and a sense that the sounds are melting together. In a recent conversation with FRIDGE, a producer I hold in high regard, he said that F1LTHY has tracks where he subjects every input to an overarching soft clipping effect.

While it is far from uncommon for soft clipping and distortion to be utilized in normative mixing and mastering processes, F1LTHY utilizes them in an unconventional extreme fashion, leveraging imbalance and obfuscation as creative tools. A snare sample begins to sound like a burst of irregularly distributed noisy frequencies – which is to say, more like itself, because that’s what basically every drum sample is in the first place. Yet he manages to turn the sound into something else, something unfamiliar and rageful, less reminiscent of previous centuries’ drum sounds.

Sub-bass is another key part of F1LTHY’s sound. The sub frequency range requires more electricity to produce than the rest of the spectrum, and its effects are famously more haptic than melodic. Taking place at 20-60 cycles per second, a sub is felt, and it occasions categorically distinct sensations in the listener, generating self-perpetuating strains of energy and involvement. Unless a sub is mixed carefully, it is liable to drown out the middle and high-frequency portions of the mix due to the sheer length of its sound waves and their appetite for sonic space. The effects of F1LTHY’s compression and distortion techniques on subs are thus all the more intense. Conventional figure/ground perspectival arrangements are unmoored by his sub-bass distortions: the boundaries of individual sounds begin to dissolve and smear together.

We can conclude that F1LTHY uses the MP3 as an instrument. His approach is remarkable because he enacts a novel interpretation of mixing and mastering, reintegrating them into the creative act as aesthetically malleable technical affordances. F1LTHY’s productions rattle their own framing, intervening at the very level of phonic materiality, experimenting with the very conditions of audition itself.

To brutally over-compress a recording in this manner is to force disintegration upon it, overloading it with sonic information so that it breaks. Attentive readers may object: Isn’t Yasunao Tone’s MP3 deviation work an obvious precedent? What about Hieroglyphic Being, Steve Poindexter, DJ Deeon? It should go without saying that there are formal precedents for F1LTHY’s production style. The difference that makes a difference is the fact that F1LTHY makes popular music, and also the specificity of his approach as compared to recent historical precedents in trap. It is also worth emphasizing that there are many other producers making strong work with comparable formal approaches to compression; the beats on ksuuvi’s new album #sameone2 are a good example.

In 2024, audio production is widely taken to be a software-specific practice. These interfaces are often skeuomorphic models of physical mixing boards, synthesizers, and effects racks. But even analog tools are exercises in virtualization: the very notion of sonic space in recorded music emerges perpendicularly from the experience of listening to music in physical space. If a mid-century recording introduces rich synthetic reverb, it contends with this experience and virtualizes the affordances of audition in a particular set of contexts: listening to big ensembles in open, social spaces such as the church, opera house, or amphitheater. If a record from the same era chooses to stylize itself as a dry recording, it follows the same protocol for smaller ensembles in less reverberant spaces such as living rooms or more compact venues. In Oliver Read and Walter Welch’s 1959 From Tin Foil to Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph, they identify these two dominant trends as “realist” and “romantic” recordings. Their criteria of measurement is spatial depth, and they argue that the distinction is drawn along racial and class lines: they identified recordings of popular music as realist, and classical music as romantic.

In the late 60s, dub reggae accomplished a Copernican refashioning of popular music’s sonic plasticity – uncovering affordances for multidimensionality where it was previously unthinkable, or merely incidental – precisely by introducing advanced mixing and mastering techniques as direct means of artistic production, hybridizing the realist and romantic. If earlier recordings tended to retain familiar-sounding sonic characteristics reminiscent of in-person performance contexts, then dub utilized advances in sound production technology to elaborate a mode of what Kodwo Eshun identifies as sonic fiction. The recording as medium becomes inextricably synthesized with composition as medium: recorded music takes leave of the world, and manipulates the affordances of the outside.

Dub demands symbiosis that externalizes the mind, drastically reconfiguring the human producer into a machine being, an audio cyborg: 'You are listenin' to a machine. I imitate human being, I'm a machine being, I don't work with human beings.' [Eshun is quoting Lee Perry.] When you sculpt space with the mixing desk, these technical effects - gate and reverb, echo and flange - are routes through a network of volumes, doorways and tunnels connecting spatial architectures … ‘I dub from inner to outer space. The sound that I get out of the Black Ark studio, I don't really get it out of no other studio. It was like a space craft. You could hear space in the tracks.’3

F1LTHY’s music speaks neither to the inside nor the outside – it is anti-architectural, flat, and despotic. He makes no attempt to fabricate a virtual space endowed with a depth-envelope in which the listener might locate themselves. It isn’t a coincidence that Carti consistently takes up baby talk in his adlibs over F1LTHY tracks, even using it in his verses – wordless, libidinal sound-assertions, brushing up against some kind of sense-making limit, as if finding oneself in and through language for the first time.

Last year, Jack Callahan released a disturbing album, Compression, riffing on computer music tropes in an attempt to process his residual loudness war trauma. The accompanying essay includes useful historical and technical analysis.

Inigo Wilkins’ remarkable forthcoming book Irreversible Noise is worth mentioning as further reading in relation to this distortion-focused section. Read my interview with him about it here.

From More Brilliant Than The Sun.